In this episode we'll focus mainly on the predynastic depictions of papyrus boats, wooden boats, the earliest depictions of the sail, and several rock petroglyphs that are quite significant to historical interpretations. Then, we'll consider a theory that has connected ancient Egypt with ancient Mesopotamia. We'll conclude by looking at a magnificent discovery at Abydos where some of the oldest wooden planked boats to have ever been found were buried in their own graves in the Egyptian desert. It's a great episode, and it's only scratching the surface of what we'll encounter as we consider maritime history in ancient Egypt.

Episode Transcript

We’re now going to turn the focus of our discussion from the maritime exploits of Mesopotamia over to the land of the pharaohs, and as we do so we’re going to turn back the clock from where it stood when we finished our look at Mesopotamia. We left Mesopotamia at a point near the decline that ensued after Hammurabi’s death, but as we enter Egypt our discussion will begin at a time prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, a time before the dynastic divisions by which we organize our understanding of the ancient Egyptians. If we had to put a date on it, the predynastic Egyptian period stretches back in time from around 3000 BCE, so pre-unification Egypt is roughly concurrent with the periods of Mesopotamia before the Sumerian dynasties.

Even in the mention of an “Upper” and a “Lower” Egypt, the current running under the surface of Egyptian history is present, and of course, that current is the Nile River, the lifeblood of Egyptian civilization for millennia. Some have called it a conduit, other have likened it to a ‘highway,’ and perhaps the most famous description comes from Herodotus where he describes the Nile as a gift-giver bestowing the gift of life upon Egypt itself. Sometimes repeated focus on the same point makes it trite, but in the case of Egypt and maritime history, the Nile really is the foundation that made Egypt a great civilization and allowed it to be on the forefront of boat technology as it developed in the ancient world.

The Nile is essentially a strip of oasis stretching for thousands of miles. It begins somewhere in the mountains of east-central Africa and from there it flows north, out of the mountains and into the desert. Scattered over the course of those several thousand miles before it branches out to drain into the Mediterranean, the Nile is punctuated by six major groups of cataracts, white water rapids or shallow stretches that are mostly impassable by boat except during flood time. The First Cataract at Aswan was the most significant of the six, and during ancient times it was a natural barrier between Egypt to its north and Nubia to its south. That’s not to say that it was categorically impassable, and pharaohs frequently pushed south into Nubia. Rather, the First Cataract at Aswan was important because early on in Egyptian history the kings fortified an island they called Abu, an island that sat in the Nile just downstream of the First Cataract and was perfectly located to serve as a choke point and transfer station for cargo being shipped on the Nile.

This island and the First Cataract were so important because north of Aswan a ship could travel unchecked to the Mediterranean along the free-flowing highway of the Nile, reaching the river’s mouth over 750 miles away. Traveling back upstream, while a bit more difficult, was relatively simple when compared to many other rivers around the globe. The whole of the journey back upstream was generally undertaken with the aid of Egypt’s predominant northerly wind, a wind blowing from north to south. In the case of the Nile, this was perfect, since the Nile flows from south to north. Later in this episode we’ll see how Egypt could well have been the first civilization to develop the sail on a wide level, and it’s likely that the complementary functions of the Nile’s flow and the northerly wind created the perfect situation for the invention and adoption of the sail.

Before we get into the specific examples that give us a window into predynastic Egypt, I also want to mention the fact that Egypt wasn’t purely limited to the north-south matrix of the Nile and into the Mediterranean. While the Nile was integral to the rise of Egyptian civilization and many of Egypt’s important features were contained within the Nile Valley, Egypt also had communication with the Red Sea to the east via the wadis that cut through the Red Sea Hills. The mountains were rich in mineral deposits and there is a wealth of evidence that the ancient Egyptians mined in the eastern mountains far back into ancient history. We’ll take a look at some rock carvings from this region that give us a glimpse at some of the oldest boat depictions on earth, but it’s important to keep in mind that Egypt did have a limited measure of contact east and into the Red Sea, though the extent of that contact is still unknown to us today.

With the geography groundwork laid, I think it’s also important to take a brief look at just how all-encompassing the Nile was in the mind of the ancient Egyptians. First off, almost all of the Egyptian creation myths had to do with the gods either being from the water or creating the earth from the water. In reality too, the Nile’s water gave life to the civilization, overflowing on an annual cycle and spreading the fertile soil that made crop growth possible along the oasis-like strip that cut through the desert. I was recently reading The Discoverers, a great book by Pulitzer Prize winning historian and former Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin. He makes the broad point that the Nile made crop growth possible, which led to an expanding civilization much like what we saw in our look at Mesopotamian growth. This growth in turn led to commerce that the Nile facilitated by being a ‘freight-way’ for transportation, not only of crops but also of the raw materials and obelisks that became symbols of Egyptian state power.

This broad point is necessary, but Boorstin makes a second fascinating point that, quite possibly, the Nile was responsible for Egypt becoming one of the first unified large-scale civilizations. He attributes that unification to the fact that the Nile floods on an annual basis, a phenomenon that led to the Egyptians delineating time in a fashion almost precisely like that of our modern calendar. Other civilizations, take those in Mesopotamia and Greece for example, those places measured time based on lunar cycles, which resulted in disparate time-keeping systems that left fragmented city-states predominant. Egypt, on the other hand, was knit together by the annual flooding of the Nile, a readily observable and actually essential occurrence that unified Egyptians in their perception of time. Now, this unification and dependence on the Nile also led to a more authoritarian power structure than those early societies, but it also gave Egypt an early edge in the ancient world.

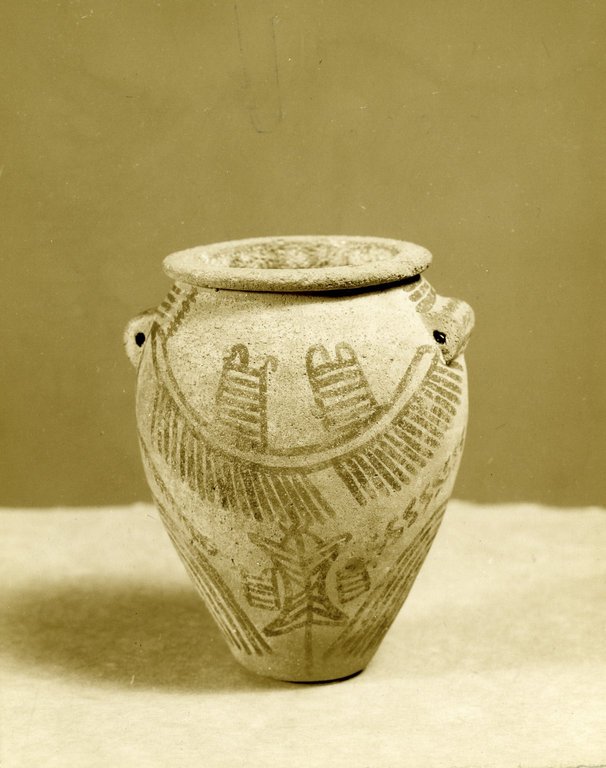

Enough of that, anyways. Now down to the nitty-gritty examples that really bring life to these somewhat abstract concepts, and we’ll start with some of the early depictions of boats from predynastic Egypt. We are forced to rely on these depictions because almost no textual evidence from such an early period has been found, and even the textual references attached to the early dynasties are still subject to debate. As would be expected, and as we saw was the case in Mesopotamia, the earliest of the Egyptian water vessels were most likely papyrus reed floats and boats. There are numerous depictions of what seem to be papyrus boats on jars and clay vases that are generally dated to the predynastic Gerzean culture, a material culture that is named after artifacts taken from a predynastic cemetery in the town of Gerzeh. The large majority of these Gerzean boat depictions are dated in the centuries around 3300 BCE and they seem to follow the general depiction of what we would expect for a papyrus reed boat: a symmetrical shape would indicate the tied off ends of the reed hull and the lines drawn downward from the hull may represent paddles or oars.

Old Kingdom linguistics also indicate that the earliest boat forms were likely papyrus boats, as the term for constructing a boat carried the concept of “binding” the boat. This term continued even after they’d also adopted wooden plank construction techniques. There is the possibility that even at this early stage the Egyptians were using wood to build their boats, as some of the depictions are asymmetrical and conform more to the structure of later wooden boats. The possibility that wooden boats were being built from the very beginning is made apparent by the reality, as we’ll see later, that even the earliest of the pharaohs had highly developed wooden ships buried in their capital cities or near their mortuary temples.

One important artifact seems to be dual proof both that predynastic Egypt used wooden boats and was among the first to develop the sail. A beautiful jar dated to the Naqada II period of predynastic Egypt depicts an elegantly shaped boat with a square sail set on a single-pole mast near the front of the boat. The boat’s asymmetrical shape seems to indicate that it was built of wood, as a reed boat of this shape with a mast pole in such a position would function poorly. Maritime historian Lincoln Paine surmises that as predynastic Egypt developed wooden boats, they mimicked the form of their papyrus boats, at first because they were inexperienced with the material, but later because they consciously sought to imitate the original papyrus boat form. It’s an interesting theory, and it’s readily apparent that wooden ships had been highly developed and come into wide use by the time of Egypt’s unification. Before we get there, let’s take a quick look at the most prevalent and the most difficult to interpret boat depictions, the petroglyphs that are scattered throughout Upper Egypt.

Although the boat depictions on the jars and vases give us a basic idea of predynastic boats and are fairly well documented, there are actually more petroglyph boat depictions than any other predynastic depiction. The problem is that the petroglyphs are less well documented, and even where there’s documentation, dating the petroglyphs is more difficult. The main informative contribution of the boat petroglyphs comes from their location, many of them in the wadis that cut through the eastern mountains to the Red Sea. While many of the wadi petroglyphs depict what we’d expect to see in a rock carving of a papyrus boat, one of the most fascinating and possibly the most important petroglyphs was recently rediscovered in the Nile village of Nag el-Hamdulab, a village that sits about 6 kilometers north of Aswan. I say the site was rediscovered because it was originally documented in the 1890s but was rediscovered in 2008 by archaeologists who went to great lengths to document the site and attempt preservation, as the site had been vandalized on at least one occasion.

The main tableaux at Nag el-Hamdulab depicts five separate boats, four of them are nearly identical in shape and size, though it’s difficult to say whether they depict papyrus boats or wooden boats, and either type would have been possible, based on the main feature of the petroglyph. That feature is the central figure who wears the White Crown of Upper Egypt, an adornment that has caused some archaeologists to associate the figure with none other than Narmer, the first pharaoh of unified Egypt. Other indicators in the tableaux further support that conclusion.

For instance, the crowned figure is being fanned by what appears to be a servant. The boats are adorned with what look to be falcon and bull insignias, and many of the predynastic boat depictions we discussed previously were also adorned with one of dozens of standards. Because the falcon and bull insignias became associated with royalty as the dynastic period progressed, it’s logical to draw the conclusion that the falcon symbol and the white crown point to the central figure as being the first pharaoh. In addition, a hieroglyphic symbol in the tableaux labels the scene a ‘nautical following,’ quite possibly a reference to the ‘Following of Horus,’ an event that consisted of the king and his royal court making journey along the Nile River Valley, most likely as a tax collection and “P.R. tour” to cement his newly won authority over all Egypt.

As fascinating as the petroglyph mural at Nag el-Hamdulab is, and as significant as its possible interpretation is, there are two other predynastic depictions I want to mention quickly before we cross over into the Early Dynastic period. The first artifact is an ivory knife-handle that was discovered in Gebel-el-Arak and is currently kept at the Louvre; the second is a marvelous painting on the brick walls of a Gerzean period tomb in Hierakonpolis, the religious and political capital of Upper Egypt as the dynastic period began. I mention these two items in conjunction because each contains a boat type similar to the wooden sailboat on the Naqada III jar mentioned earlier, the dark colored sleek boats with one high vertical end. The boats on the Gebel el-Arak knife handle actually have two symmetrical high ends, a trait that is generally associated with Mesopotamian boats from the same period. The Hierkanopolis tomb painting depicts a flotilla of six boats. Five of them are readily identified with the common Egyptian papyrus reed boat of predynastic times, but the sixth boat is nicknamed the ‘black boat’ because it is quite unique. It has one high vertical end and an oar near the front, unique traits that have led some scholars to call it a foreign boat.

Now, at one point the knife handle and the tomb painting were interpreted together as depicting the same event, a late predynastic invasion of people from the east. The foreign invaders were once thought to be Mesopotamian in origin, and while that theory has been dismissed, it’s still possible that the ‘foreign’ boats depict Mesopotamian vessels. The theory that resonates most with me is that even in predynastic Egypt, both Egypt and Mesopotamia had trade contacts with people in the Levant. Egyptian inscriptions bearing the name of Narmer have been discovered in the Levant, and it’s feasible that both cultures had interaction there, and that the distinctive design of the Mesopotamian boats made it’s way to Egypt, not via invasion, but rather by Egyptian artists using the design on depictions that eventually found their way down the Nile to Upper Egypt. This interpretation seems more likely than the invasion interpretation because very few physical artifacts related to Mesopotamia have been found in Upper Egypt, the place that was supposedly invaded by Mesopotamian sailors. Those that have been found could easily have made their way there via trade exchanges.

So, while claims of Mesopotamian invasion seem dubious, Egypt certainly had trade connections with the Levant and even out into the Red Sea. They also seem to have had maritime connections south into Nubia, despite the cataract at Aswan. A beautiful incense burner unearthed at a royal tomb in the Nubian town of Qustul is unquestionably carved in a Nubain artistic style, but it depicts imagery that is readily associated with Egyptian royalty. The carved image encircling the incense burner depicts what seems to be a royal boat procession, with a seated figure again wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt in the central boat. The forward-most boat contains a prisoner, and the boat appears to contain a square sail set on a single mast, similar to the design of the Naqada II jar. Because the boats are en route to a palace-like structure, the incense burner has been interpreted as depicting a royal procession, possibly again the ‘Following of Horus.’

All right. That’s as much as we’ll consider when it comes to the predynastic period. There’s so much more that could be said and speculated about, I mean, there are entire books dedicated to predynastic boats in Egypt, but I think we’ve hit the highlights that give us a good base to transition into the Dynastic period. As we’ve seen, the first named pharaoh and the one responsible for unifying Upper and Lower Egypt was Narmer, sometimes called Menes. I’ll try not to get too sidetracked by the political history of Egypt, and if you’re interested in the subject I’d recommend Toby Wilkinson’s Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt as a concise glimpse at the high points of Egyptian history. We’ve already seen how Narmer’s name has been found in the Levant, and how other evidence seems to indicate that he also extended his reach south into Nubia. Those facts being the case, it’s fairly safe to assume that by the start of the dynastic period Egypt had already developed wooden boats to a useable degree. Nothing confirms that theory more than a discovery that was made in the ancient Egyptian city of Abydos. Abydos has been called the “Giza” of the early dynasties; it was the focus of technological innovation and religious development, early iterations of pyramid-like burial structures have been found there, and the Royal Necropolis at Abydos was the resting place of the first pharaohs.

The maritime relevant discovery at Abydos technically came from the royal necropolis called Umm el-Qa`āb, which is located about a mile outside the ancient city itself. With it’s imposing temples and wealth of artifacts, Abydos has been the focus of excavation and archaeological work since the inception of modern Egyptology. In 1988, Australian Egyptologist Dr. David O’Connor was leading a team at Abydos when they discovered a burial mound which he theorized to be a proto-pyramid. During the same season, they discovered lines of mud brick buried beneath the sand. Although they initially assumed that the brick structure was the corner of a yet undiscovered enclosure, when they returned to uncover the remaining portion three years later, they made what O’Connor called a “startling and significant discovery.”

As digging progressed, the team realized that they were unearthing a series of oddly shaped walls, each one running in the same direction, perpendicular to where the Nile flowed 7 miles to the west. Soon, however, the team realized that these ‘walls’ were something else altogether. In reality, the walls turned out to be boat graves, 12 of them discovered in 1991 alone, and several more later on. The archaeology team wasn’t far off in their original assessment though, because the boats themselves were each enclosed within a brick casing, and, although the brick enclosures were low-lying, once they were uncovered, their boat-like shape was unmistakable. Further examination revealed facts that give us a picture of what the fleet would have looked like several thousand years ago. Each grave had originally been coated in mud plaster and painted white, so an Egyptian at Abydos would likely have seen a fleet of huge boat-shaped enclosures sitting out in the desert, reflecting the bright desert sun. Small boulders placed in similar locations near the prow or stern of many of the boats seem to indicate a ceremonial ‘mooring’ of the boats to the desert floor, their sterns all in a line, pointed toward the Nile in the distance.

The whitewashed brick enclosures have been said to look like a ghostly fleet anchored in the Egyptian desert, but the boats contained within the enclosures give us an amazing window into just how advanced Egyptian boatbuilding had become by the time of the second dynasty. The boat graves at Abydos have been dated to the reign of Khasekemwy, who was the last pharaoh of the second dynasty, he ruled and the most of the boats were probably buried somewhere around 2175 BCE. Anyway, following the original discovery, another 10 years passed before the team could arrange the approvals and necessary preservation measures needed to make excavation of a boat grave feasible. In 2000, Dr. O’Connor led an excavation that confirmed the hopes they’d harbored throughout the 90s. Each boat grave contained a wooden planked boat that conformed to what the brick enclosures indicated; from the outside, the graves were enormous, their average length measuring in at almost 90 feet, or 27.5 meters, and that despite their narrow width, the widest boat measuring about 10 feet.

The most important information though came from the wood itself and the graves that had not been worn down preserved their contents in an amazing fashion. This preservation was accomplished by the way in which the boats were basically sealed in their graves; a narrow trench was cut in the sand, and the boat’s wooden hull then nestled down in the sand. The brick enclosure was then built up around the boat, the inside edge built to conform to the shape of the hull. Several of the boats had the inside of the hull filled in with mud brick, and all of the boat graves were then sealed with mud plaster and painted white. The wood used to build the boats seems to have been locally sourced, in contrast to the Lebanon cedar-wood that came to be used later in Egyptian history. The construction of the boats was accomplished using thick wooden planks that were lashed together by rope fed through mortises. The seams between the planks were filled with bundles of reeds, and more reeds carpeted the floor of the boat. These early boats were not built with internal frames, and some of the boats appear twisted or lopsided, the common fate suffered by vessels without an internal structure to support them out of the water. Pigmentation on the boats seems to show that some of several of them were painted white, while at least one was painted yellow.

I’d like to wrap up our look at the earliest maritime evidence from Egypt with a revealing quote from Dr. O’Connor in which he summarized the significance of the Abydos boats. He said:

”Ancient Egypt is a riverine civilization, yet before these boats were discovered, we knew very little-beyond representations on ancient pots-about ancient Egyptian boats earlier than the reign of Khufu, one of the greatest fourth dynasty pharaohs. These boats provide us with a window into better understanding Egypt at the dawn of its extraordinary, long-lived civilization. Moreover, recent excavations have confirmed our original guess. These boat graves contain actual and viable boats intended for a king's use in the afterlife. They are in meaning and function the direct ancestors of the famous boat recovered at Khufu's Great Pyramid at Giza and predate Khufu's boat by perhaps as much as 300 years.”

- O'Connor, David, Boat Graves and Pyramid Origins: New Discoveries at Abydos, Egypt, Expedition, Vol. 33, No. 3 (1991), pp. 5–15.

I should note that other early boat graves have been discovered at Helwan and Saqqara, two sites connected to the ancient capital of Memphis, but next time we’ll turn our focus to the Khufu ship that Dr. O’Connor alluded to in that quote. The ship is one of the most beautiful and important maritime discoveries from Egypt’s Old Kingdom, perhaps even the entire ancient world, and it’s an episode that I particularly enjoyed putting together. It’s one artifact alone, but it’s size, technicality, and importance justify devoting an entire episode to it.

Sources

- Boorstin, Daniel J., The Discoverers: A History of Mankind's Search to Know His World and Himself (1983).

- Breasted, James Henry, The Earliest Boats on the Nile, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 4, No. 2/3 (Apr. – Jul., 1917), pp. 174–176.

- Casson, Lionel, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World (1995).

- Dagger from Gebel el-Arak, Predynastic Egypt, Louvre. [link]

- Decorated vase, Predynastic Egypt, Brooklyn Museum. [link]

- Decorated Ware Jar Depicting Ungulates and Boats with Human Figures, Predynastic Egypt, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [link]

- Hendrickx, Stan, John Darnell, Maria Gatto & Merel Eeyckerman, Iconographic and Palaeographic Elements Dating a Late Dynasty 0 Rock Art Site at Nag el- Hamdulab (Aswan, Egypt), in International Colloquium, The Signs of Which Times? Chronological and Palaeoenvironmental Issues in the Rock Art of Northern Africa, Royal Academy for Overseas Sciences, Brussels, 3-5 June, 2010, pp. 295-326.

- Herodotus, The Histories, (Macaulay's English translation, republished 2004).

- Jar with boat designs, Predynastic Egypt, Brooklyn Museum. [link]

- McGrail, Seán, Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval

Times (2009). - McGrail, Seán, Early Ships and Seafaring: Water Transport Beyond Europe (2015).

- New York University, After 5,000 Year Voyage, World's Oldest Built Boats Deliver – Archaeologists’ First Look Confirms Existence Of Earliest Royal Boats At Abydos, ScienceDaily, 2 November 2000. [link]

- O'Connor, David, Boat Graves and Pyramid Origins: New Discoveries at Abydos, Egypt, Expedition, Vol. 33, No. 3 (1991), pp. 5–15.

- Paine, Lincoln, The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World (2013).

- Qustul Incense Burner, Nubia, The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. [link]

- Sailing ship jar, Naqada II, Egypt, The British Museum. [link]

- Storemyr, Per, The Palaeolithic rock art in Wadi Abu Subeira, Egypt: Landscape, archaeology, threats and conservation, Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation, 1 May 2012. [link]

- Vinson, Steve, Boats of Egypt Before the Old Kingdom, (August 1987) (M.A. Thesis, Texas A&M University).

- Vinson, Steve, Boats (Use of), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles (2013).

- Ward, Cheryl, Boat-building and its social context in early Egypt: interpretations from the First Dynasty boat-grave cemetery at Abydos, Antiquity, Vol. 80 (2006), pp. 118–129.

- Ward, William A., Relations between Egypt and Mesopotamia from Prehistoric Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Apr., 1964), pp. 1–45.

- Wilford, John Noble, Early Pharaohs' Ghostly Fleet; Archaeologists Excavate Boats That Carried Kings to the Afterlife, N.Y. Times (Oct. 31, 2000).

- Wilkinson, Toby, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt (2010).

4 Responses

The podcast says that the incense burner of Qustul depicts a seated figure wearing the white crown. However when you look at the actual incense burner fragments there is no seated figure. A missing fragment that was never recovered is claimed by Bruce Williams of the Oriental Institute to have shown a seated figure. What appears on the incense burner is a shape he claims is the white crown but it is speculation. The shape is on a 45 degree angle which would be unusual for someone wearing the crown and if a figure was seated below it the figure would have to be of a child’s proportion to fit. It may be a white crown it may not be. It is a simple shape unlike the more distinctive red crown on other art. Below that fragment with that shape on it is a big gap, the location of the unfound missing fragment.

The yellow illustration from the Oriental Institute represents what is on the incense burner along with Bruce Williams conjecture that there is a seated figure there. You can see a line of demarcation in the illustration. What is claimed to be a falcon is similarly unclear. A bull and other figures are clear though.

It’s a misleading presentation from the Oriental Institute because they don’t make clear what is actual and what is guessed clear in the illustration. It takes a while to understand and notice the demarcation line and recognize it is a demarcation line not a line like the other lines.